[Note: Because my website remains in shambles following server failures, I will post here (for the first time since 2011) until those issues are resolved]

Since Muhammad Ali's death days ago I have been debating whether to address this - and if so, when. Reading various accounts mention Ali's relationship with the legendary hustler Major Coxson, some of which make unsupported allegations against Ali and many of which are superficial (in addition to others which ignore the consequential ties between the two), makes me think it is best to pen something now in the hopes of correcting the historical record in a timely fashion.^

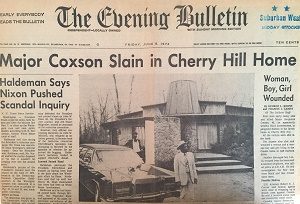

On June 4th, for example, the

New York Times had a commentary which included this line: "Ali sometimes fell in with the wrong crowd, including his friend Major Coxson, a politician and gangster in Cherry Hill, N.J., who was killed in a 1973 mob hit." [Also, e.g., see

here.]

I would be very interested in knowing how many Times readers had a clue what was being discussed. Who was Coxson? How close a friend was Coxson to Ali? What mob? What mob hit? Was Ali, himself, ever a target, and/or was he otherwise involved in that edgy and violent scene?

The answers to those compelling questions fill many pages of

my work on Philadelphia's Black Mafia over the past 20 years, and I have been asked many times about the boxing legend's involvement: with Coxson; with Philadelphia's underworld; and with the leader of the Nation of Islam's infamous Temple 12, Jeremiah Shabazz (a man

The New Yorker said this week was "not someone you'd ever wish to offend" -

did readers ever pause to wonder why?). Unfortunately for someone trying to get a concise read on this complex and controversial history, these issues are all inter-related and thus require considerable explanation.

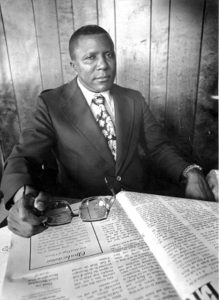

In 1958, Philadelphia-born Jeremiah Shabazz (formerly known as Jeremiah Pugh), was promoted to Minister of the Nation of Islam's Temple 15 in Atlanta and soon became the NOI's Minister of the Deep South, responsible for Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. In 1961, Shabazz was asked to help the NOI's Minister in Miami, Ishmael Sabakhan, court Cassius Clay to the Nation of Islam. As Shabazz said of the early meetings with Clay/Ali,:

...he didn't have any problems with our claim that the white man was evil. Sometimes he'd ask questions like, 'Wait a minute, how about a baby? A baby is born white. How is it the devil?' And I'd explain, if a lion gives birth, it can't give birth to anything except a lion...This was in 1961 when a lot of outright injustice was going on. You could see it...And the thing that really got Cassius was when we began to explain that, for someone to do this to other human beings, they can't be what they thought they were. They can't be God's people and mistreat other people the way white folks were doing.¹

Clay began attending NOI meetings somewhat frequently and surreptitiously and attempted to keep his conversion a secret. As David Remnick wrote, "(Ali) was well aware that the few white people who did know something about the Nation of Islam saw it as a frightening sect, radical Muslims with a separatist agenda and a criminal membership."² As is now widely known, Ali publicly disclosed what had by then become obvious on February 26, 1964, the day following his momentous victory over Sonny Liston in Miami.

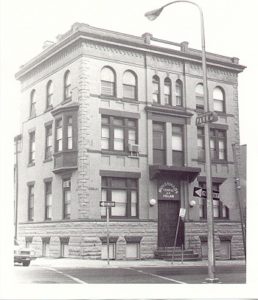

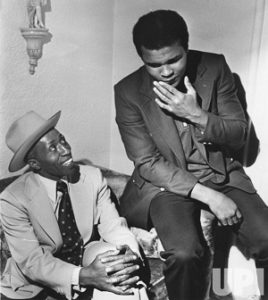

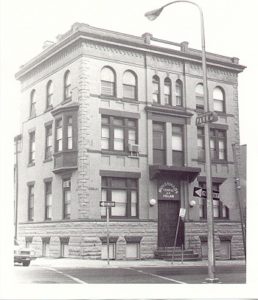

Jeremiah Shabazz returned to Philadelphia to head Temple 12 in April 1964, and by then was one of NOI leader Elijah Muhammad's closest advisors. With the help of Ali, who often traveled with Shabazz during recruitment and enlightenment drives along with speaking at special events, Temple 12 boomed under his leadership (by the end of the decade, membership was estimated at 10,000).

As Temple 12 thrived, a powerful crime syndicate calling itself the Black Mafia was forming with some of the city's most dangerous and feared among its founders. Of particular relevance to the Ali-Philly underworld-Coxson circumstances, most of the Black Mafia's leaders and heavyweights were major players in Temple 12 under Shabazz. In fact, Temple 12's Fruit of Islam - the paramilitary guard responsible for protecting Shabazz and the mosques, among other duties - was full of Black Mafia thugs with lengthy and violent criminal records.

An ultra-violent group formed in the early to mid-1960s, Philadelphia's Black Mafia's primary enterprise was extortion, almost exclusively of illicit entrepreneurs like drug dealers and nightclubs which permitted/embraced dubious activities such as gambling and prostitution (i.e., persons who would not report the Black Mafia shakedowns to authorities). In time, the group (which also pilfered significant government funds ostensibly designed to stop gang warfare) was overseeing entire sections of the city and venturing into extorting legitimate businesses; in short they were engaged in all sorts of mayhem throughout the city, its suburbs, South Jersey, and Delaware. There is far too much to write about Philly's Black Mafia in that regard here, but for the reader unfamiliar with the murderous group it is instructive to note they killed dozens of people - targets and often those with them at the time of slayings (typically family members). Victims, targets, and - especially - witnesses of the group's multifarious misdeeds were properly frightened and thus didn't report most crimes, furthering the syndicate's street legend and reach.

The Black Mafia devised financial hustles and committed assorted acts of violence along the Eastern seaboard, accounting for some of the region's most notorious crimes to date including the January 1973 Hanafi slayings. The Hanafi incident in Washington, DC (DC's largest mass murder, which included the drowning of four children ranging from nine days to 22 months old) involved a feud between the Nation of Islam and its former national secretary (known then as Ernest 2X McGee), Hamaas Abdul Khaalis, who since leaving the Black Muslim movement had loudly rejected the NOI, generally, and Elijah Muhammad, specifically. Eight Black Mafia members were sent from Philly's Temple 12 to kill Khaalis over a vitriolic letter he had sent to all 56 NOI mosques, but Khaalis wasn't home and the hit squad killed seven others (including the babies) instead.

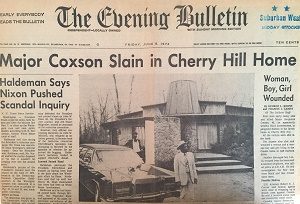

This verbose backdrop offers a sense of the heady times and especially of the tensions. So, who was Major Coxson, and what was Ali's role in his life and career, resulting in the recent New York Times mention and others?

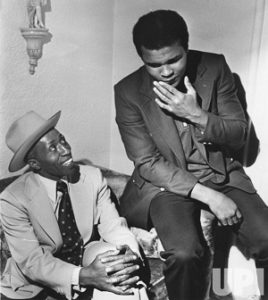

Major Benjamin Coxson was born in 1928 and moved from Western Pennsylvania to North Philadelphia in 1942. His life in Philadelphia was one filled with smiles, flamboyance, suspicion, and arrests. A career con man, Coxson's impressive criminal record by 1970 included 17 arrests for thefts and frauds, involved one stint in federal prison, and yet no crimes of violence. Perhaps it was for the latter reason he was permitted to be a mainstay on the city social scene where he was involved (formally or otherwise) in bars and nightclubs, popular with politicians (with whom he openly was seen and for whom he campaigned) and sports figures and gangland figures of all stripes. He was described as having a wide, toothy smile, and the mention of his name often drew chuckles from those who knew him. Law enforcement intelligence and surveillance reports described Coxson routinely hanging with Black Mafia members and affiliates, along with his "drug apartments" which were used alternately as safe houses and by celebrities for various purposes. Despite being a drug financier and the middleman between disparate organized crime syndicates (in Philly and New York), The Maje, as he was often called, was a fixture in the media and commonly graced covers of local publications. Major Coxson's close friendship with Muhammad Ali was a prime reason for the coverage.

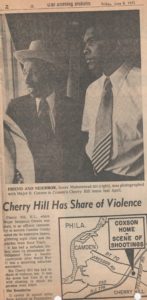

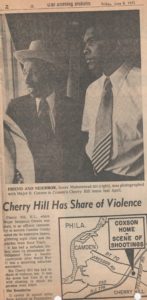

Major Coxson first met Muhammad Ali in 1968 when the boxer was in Philadelphia raising funds for a neighborhood organization called the Black Coalition, whose board included close Coxson friends and Ali's friend and mentor, Jeremiah Shabazz. Coxson and Ali would be in each other's company frequently over the next several years, and their relationship was often mentioned in the press. For example, it was reported that Coxson became Ali's agent in October 1969, and Ali purchased Coxson's lavish home in the Overbrook section of Philadelphia in 1970.

According to Ali, when he was deciding to relocate from Chicago to somewhere closer to New York City, he chose Philly in part because of Coxson's pitch, joking "The Major made me move to Philadelphia."

Ali then moved roughly a year later when he purchased another home from Coxson, this time in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. In fact, when he sold his Spanish-style home on Winding Drive in Cherry Hill to Ali, Coxson simply moved a few blocks away to Barbara Drive and the two became neighbors. Some may recall Coxson's 1972-3 campaign for Mayor of Camden, New Jersey.

The mayoral run, announced in January 1972, began publicly with a grand party at the area's largest nightclub, the Latin Casino in Cherry Hill, with Muhammad Ali in attendance and the 2300 guests treated to performances by The Supremes and the Temptations. Coxson was fond of saying, “Muhammad Ali will add a real punch to the campaign.” Unfortunately for Coxson, starting in March 1972 the IRS began confiscating his fleet of luxury vehicles because he owed $135,000 in back taxes.

Coxson responded by purchasing a tandem bicycle and placing his chauffeur, Quinzelle Champagne, in the rear for a great publicity stunt.

Ultimately, Muhammad Ali donated a silver Rolls Royce for Coxson to use, and the boxing star was a mainstay throughout the campaign. For instance, in June 1972, moments after his defeat of Jerry Quarry in Las Vegas, Ali dedicated the victory "to the next mayor of Camden, New Jersey, Major Coxson." Furthermore, the February 1973 grand opening of a hardware store in the Germantown section of Philadelphia featured Ali and “the incomparable Major Coxan [sic].” On March 31, Ali mugged for the cameras with Coxson at ringside before his bout with Ken Norton in San Diego, and told the assembled media that Coxson was his “unpaid financial adviser.” Six days before the May 8 election, Ali joined Major Coxson at his “victory” party.4

Among the many great quotes uttered by Coxson during the months of considerable campaign press attention, was this, offered in response to the constant questions about his criminal background and associations: "I'm no priest, but I'm not the devil, either. In New Jersey, most office holders start as politicians and wind up being arrested. I thought I'd reverse the trend."5 As a too-perfect ending to the mayoral campaign, Coxson lost the May 1973 race in a landslide to Angelo Errichetti...who proved Coxson right about New Jersey office holders starting as politicians and winding up being arrested when

Errichetti was arrested and convicted for his role in ABSCAM. [Note:

Errichetti was portrayed by Jeremy Renner in the 2013 film American Hustle]

Not long before Coxson lost the election, a $1 million heroin shipment from the Gambino Crime Family in New York to the Black Mafia was stolen. The Gambinos offered Coxson $300,000 to locate the stolen narcotics and/or the persons responsible. Coxson accepted the deal, and enlisted his Black Mafia pals as subcontractors, so to speak, whereby broker Coxson would only keep $100,000 of the agreement. For reasons that remain unclear, the Black Mafia executed the two men believed responsible for the theft and their bodies were discovered on May 1, 1973. The Gambinos, realizing they would not recoup the drugs or the expected funds and that such high-profile murders would bring law enforcement attention, stiffed Coxson, arguing the services provided weren't what they requested. Problematically for Coxson, the Black Mafia still expected the promised $200,000. Coxson spent weeks unsuccessfully trying to come up with the cash; the clock was ticking on The Maje's life.

In the early morning hours of June 8, 1973, four Black Mafia members visited Coxson's futuristic-looking home in an upscale leafy section of Cherry Hill (about a ten-minute walk from Ali's house, the one he purchased from Coxson). Coxson lived with his common-law wife and her three children. All five occupants were bound with hands and feet behind them (neckties were used), and as the executions were about to begin one child was able to escape - though still bound with neckties, he hopped to a neighbor's home. The remaining four victims were each shot in the head and left for dead by the hit squad. When police arrived, they found Major Coxson dead, kneeling next to his bed bound and gagged and shot three times in the head at close range. His partner survived, though was left blinded, as did her one son who remained in the home. Her daughter died of her wounds four days later.

Because of his close relationship with Coxson, law enforcement officials initially feared for Muhammad Ali's safety. Ali, however, said concerns for his safety were simply rumors “probably [started by] some white man who doesn’t like me because I got two Rolls Royces, a $200,000 house, and I talk too much for a nigger.”6 Incredibly, Ali immediately began distancing himself from Coxson, and stated among other things, “Coxson was a good associate of mine, not a true friend. The Koran preaches that only a Muslim can be true friends with another Muslim, and Coxson was not a Muslim.”7

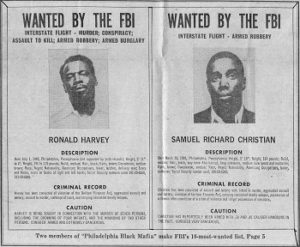

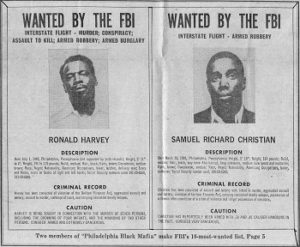

At the time of his death, Coxson was the target of several criminal investigations, involving tax evasion, possession of stolen or counterfeit credit cards, narcotics trafficking, and involvement in a Pennsylvania-New Jersey car ring, and was on the verge of being indicted according to authorities. The Coxson slayings (in part because of Coxson's stature and in part because of his close ties to Muhammad Ali) were national news and again placed Philly's Temple 12 in the spotlight. When Jeremiah Shabazz was asked about the role of Black Mafia hit men in his mosque, he originally said he'd prefer to not address the matter, and later stated, "Some of the alleged Black Mafia members came out of my temple but I would no more accept responsibility than the Catholic priests would accept responsibility for the Mafia."8 Because of the Hanafi and the Coxson slayings, two Black Mafia leaders were placed on the FBI's Most Wanted List in December 1973 [Note: in addition to

my written work on these matters, both incidents are further examined in

this television show].

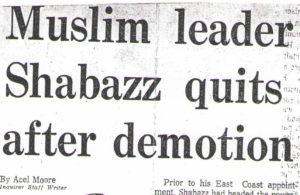

Following the February 1975 death of NOI leader Elijah Muhammad, his son, Wallace Muhammad, began a series of reforms called "The Second Resurrection" which included purging the criminal element from the NOI and, most controversially, integrating whites into the mosques; the Black Muslim movement fragmented with various sects and leaders evolving. Muhammad Ali opted to follow Wallace and embraced a more inclusive form of Islam. Interestingly, Jeremiah Shabazz was demoted by Wallace Muhammad from his perch at Temple 12 (then commonly known as the "Hit Mosque" and the "Hoodlum Mosque" because of the many high profile Black Mafia activities) as part of the reform movement.

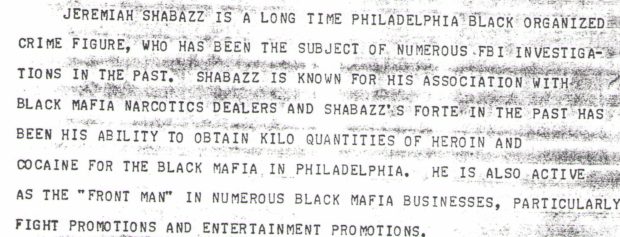

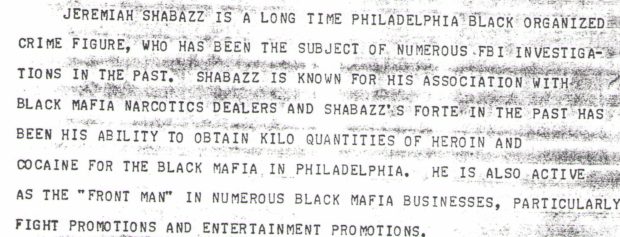

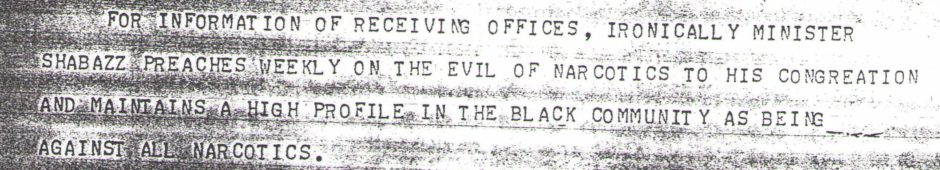

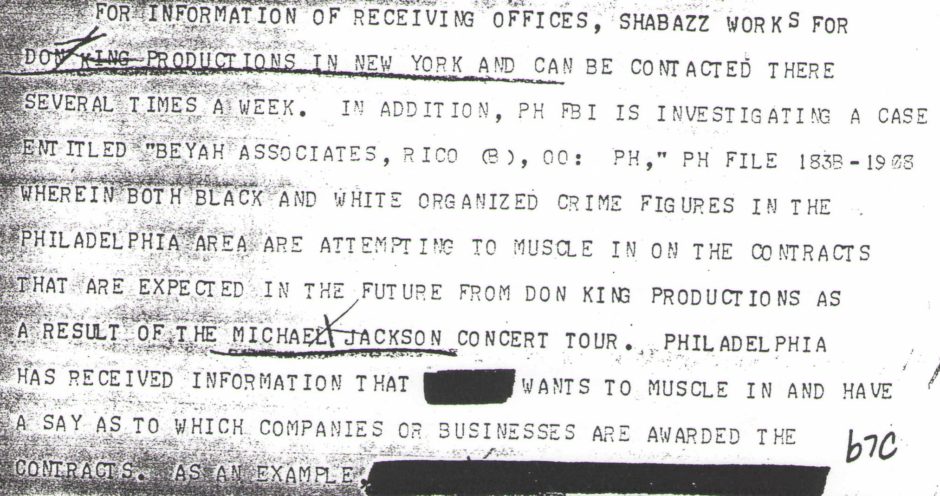

Jeremiah Shabazz is a major black organized crime figure in the Philadelphia area who associates with both black OC figures and Philadelphia’s LCN [La Cosa Nostra]. In addition, he maintains a high profile in the Philadelphia area through his image as a religious leader and through his contact with Don King Productions and major entertainment stars, when in fact, he is a narcotics trafficker who utilizes both his religious background and business associates as a cover for his illegal activities.

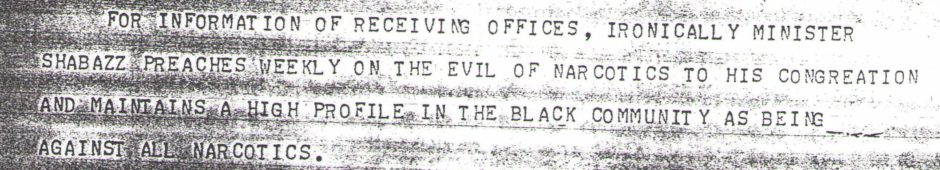

Another related teletype contained this:

Additionally:

The FBI's strategy in this aspect of their large investigation was to develop a case against Shabazz strong enough to ensure his cooperation. The FBI wrote, “Once Shabazz supplies the one quarter ounce, [the FBI’s field office in] Newark will approach him for his cooperation in continued investigation of drug matters and organized crime activity.” Specifically, the FBI believed that if Shabazz agreed to cooperate, he “very likely could provide information … [concerning] Black Muslim trafficking in heroin and cocaine in the Philadelphia area [and] narcotics dealing between the Black Muslims and the … LCN organization in the Philadelphia/Atlantic City area.” The FBI's long-planned/negotiated heroin buy took place on December 1. 1984, but Shabazz was never charged in the drug conspiracy case. The FBI does not comment on whether individuals have cooperated and we are left to speculate regarding the case's resolution re: Shabazz (a review of the voluminous Shabazz FBI FOIA file is instructive; several other targets were successfully prosecuted as a result of the multi-jurisdictional probe).

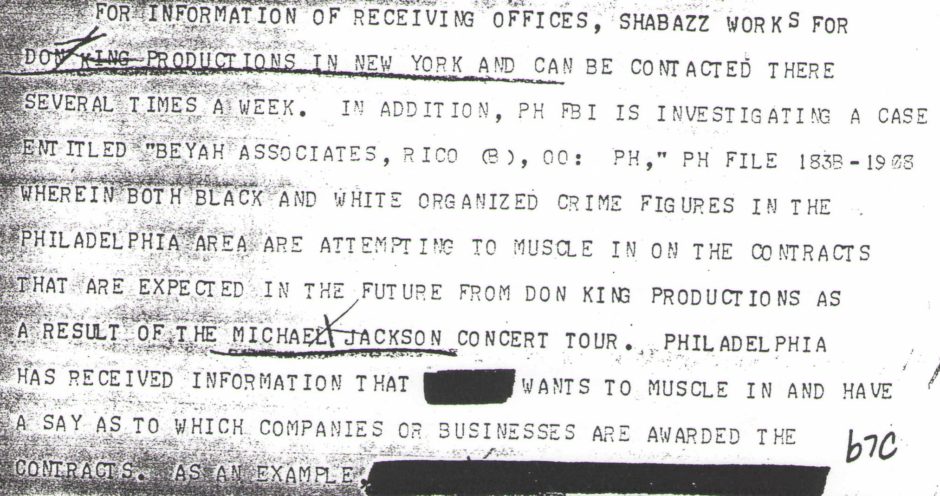

During the Shabazz-related federal narcotics investigation, authorities caught wind of extortion efforts in Philadelphia regarding the Jackson's 1984 Victory Tour.

The details remain murky but the press conference describing the resolution of whatever behind-the-scenes troubles is telling. Jeremiah Shabazz and Don King (

the tour's promoter) agreed to terms with a popular, longtime Philadelphia disc jockey and activist named

Georgie Woods. When Woods announced that he had agreed to terms with the Jacksons he did so accompanied by his “spiritual adviser,” Shamsud-din Ali. Importantly, Shamsud-din Ali, who took over Temple 12 following the demotion of Jeremiah Shabazz, was a Black Mafia leader formerly known as Clarence Fowler. Fowler (who was a captain in the FOI under Shabazz at the time) was convicted of a 1970 murder and served a few years in prison before his conviction was overturned by a divided Pennsylvania Supreme Court (a re-trial was ruled out by officials when the key witness against him refused to participate, supposedly after being visited by Black Mafia henchmen); he returned to the streets as Shamsud-din Ali. [Please see

* below for more relevant information and context re: Shamsud-din Ali]

So...

It is certainly the case Muhammad Ali was very close with two individuals - Major Coxson and Jeremiah Shabazz# - who were wholly immersed in the social system of Philadelphia's Black Mafia. Critics of Ali make a fair point when they argue his high-profile embrace of Coxson and of Shabazz enhanced their credibility within certain circles - confusing and intimidating people - possibly even resulting in victimization of which Ali may never have been aware. However, I'll end with something I first attempted to address back in 1999 because it remains true to this day (which is important given all I have reviewed and learned since), and it matters in light of all I have written above:

While Muhammad Ali certainly traveled with an interesting and dangerous crowd in Philadelphia and South Jersey, there remains no suggestion, let alone evidence, of any wrongdoing on Ali's part. Examinations of surveillance records and other intelligence documents, many of which include analyses specifically of the boxing legend, do not reveal a single item relating to dubious activities by Ali.

spg

^ Unless stated otherwise, all commentary and supporting evidence can be found in Sean Patrick Griffin,

Black Brothers, Inc.: The Violent Rise and Fall of Philadelphia's Black Mafia (Leicester, UK: Milo, 2007). Please note that although they make for choppy reading and an even more amateurish look I have included the images from press coverage to demonstrate how widely-known most of this was at the time the various events transpired.

* Immediately following Clarence Fowler's 1976 release from prison (now as Shamsud-din Ali) informants described Shamsud-din continuing the Black Mafia extortion racket, and in the late 1990s he became the subject of a massive federal narcotics investigation when wholesalers for

a drug-dealing rap group (with Black Mafia origins) named RAM Squad discussed his alleged role on wiretaps. That probe involved an overheard conversation of Shamsud-din asking a drug wholesaler for $5,000, explaining he needed the money to give to a longtime aide to Philadelphia Mayor John Street. The revelation spawned a separate and distinct investigation into municipal corruption that involved "pay-to-play" shakedowns and "no-show" jobs; it was discovered Shamsud-din was a major power broker in municipal contracting and

his stature was acknowledged by politicians and by violent entrepreneurs, alike. Concerning the latter, Dawud Bey (son of founding Black Mafia member Roosevelt "Spooks" Fitzgerald) was recorded complaining to another prominent drug dealer that Shamsud-din was "walking with kings and we're out here hustling." Bey was likely referring to Shamsud-din's prominence in city politics, which included things like meeting President Bill Clinton during a visit with Mayor Street. The drug investigation led to the convictions and/or guilty pleas of 37 people, and the corruption probe resulted in another 20 persons pleading guilty or being convicted at trial, including the City Treasurer. In 2005,

Shamsud-din was convicted of 22 counts of various racketeering and fraud charges and was sentenced to seven years and three months in prison; he was released from federal prison in December 2013.

As is so often the case with this history, there is a degrees-of-separation worth noting considering the genesis of this post, namely Muhammad Ali's involvement in the Black Mafia's social networks. Among those convicted in the corruption probe with Shamsud-din was his daughter, Lakiha "Kiki" Spicer,

who was found guilty (along with her mother and Shamsud-din's wife, Faridah Ali, formerly Rita Spicer) in October 2004 for her role in a "ghost teacher" scam. Incredibly, Kiki (after dating a RAM Squad member and drug dealer named Tommy Hill - birth name John Wilson -

who was later killed in 2011 when it was disclosed he had cooperated with authorities)

went on to marry boxing great Mike Tyson in June 2009. She met Tyson when she was 18 years old because of Shamsud-din's relationship with Don King and thus she often attended boxing events.

Said Don King to Mike Tyson about dating Shamsud-din Ali's daughter, "Stay away from her. Don't go talking to that girl. Leave these people alone. These are not people to mess with." Despite Don King's warning, Kiki,

who discovered she was pregnant with Tyson's child a week before she entered federal prison in April 2008 (she was released on October 30, 2008), wedded Tyson and the couple have two children together.

1. Thomas Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (New York: Touchstone, 1991), p.93.

2. David Remnick, King of the World (New York: Random House, 1988), p. 135.

3. Bruce Keidan, “Police Protection Fails to Lessen Faith in Religion,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 13, 1973.

5. Donald Janson, "Camden Mayoral Hopeful Runs a Flamboyant Race," New York Times, April 7, 1973, p. 77.

6. "Muhammad Ali Next? He Blames Crank for Rumors," Philadelphia Inquirer, June 15, 1973.

7. James Nicholson, "The Underworld on the Brink of War: Part I - The Muslim Mob Gets It On," Philadelphia Magazine, November 1973, p. 220.

8. Les Payne, "The Man Who Drew Cassius Clay to Islam," Newsday, February 16, 1997, p. G06.

.png)

As Temple 12 thrived, a powerful crime syndicate calling itself the Black Mafia was forming with some of the city's most dangerous and feared among its founders. Of particular relevance to the Ali-Philly underworld-Coxson circumstances, most of the Black Mafia's leaders and heavyweights were major players in Temple 12 under Shabazz. In fact, Temple 12's Fruit of Islam - the paramilitary guard responsible for protecting Shabazz and the mosques, among other duties - was full of Black Mafia thugs with lengthy and violent criminal records.

As Temple 12 thrived, a powerful crime syndicate calling itself the Black Mafia was forming with some of the city's most dangerous and feared among its founders. Of particular relevance to the Ali-Philly underworld-Coxson circumstances, most of the Black Mafia's leaders and heavyweights were major players in Temple 12 under Shabazz. In fact, Temple 12's Fruit of Islam - the paramilitary guard responsible for protecting Shabazz and the mosques, among other duties - was full of Black Mafia thugs with lengthy and violent criminal records.

Of note, it was Khaalis who converted UCLA basketball star and NBA rookie Lew Alcindor to Sunni Islam, and to practicing a strand founded by Abu Hanafa (hence the followers were called Hanafi Muslims). Alcindor of course became Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and in those days he feuded with Ali openly. Abdul-Jabbar was quoted as saying, "They visited me. I was taken to dinner by one of their ministers and Cassius Clay.” His use of Ali’s former name was not inconsequential, and signified the bitter divisions within America’s various Muslim sects back then. “I’ll call him Cassius Clay or Cassius X,” said Abdul-Jabbar, “but not by the name of the prophet. He is not a Muslim.”³ Interestingly, the Hanafi slayings took place in a mansion donated to Khaalis by Abdul-Jabbar, who received police protection for a time following the murders. [Authorities never officially concluded who ordered the slayings, and neither Elijah Muhammad or Jeremiah Shabazz was implicated in the crimes.]

Of note, it was Khaalis who converted UCLA basketball star and NBA rookie Lew Alcindor to Sunni Islam, and to practicing a strand founded by Abu Hanafa (hence the followers were called Hanafi Muslims). Alcindor of course became Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and in those days he feuded with Ali openly. Abdul-Jabbar was quoted as saying, "They visited me. I was taken to dinner by one of their ministers and Cassius Clay.” His use of Ali’s former name was not inconsequential, and signified the bitter divisions within America’s various Muslim sects back then. “I’ll call him Cassius Clay or Cassius X,” said Abdul-Jabbar, “but not by the name of the prophet. He is not a Muslim.”³ Interestingly, the Hanafi slayings took place in a mansion donated to Khaalis by Abdul-Jabbar, who received police protection for a time following the murders. [Authorities never officially concluded who ordered the slayings, and neither Elijah Muhammad or Jeremiah Shabazz was implicated in the crimes.]